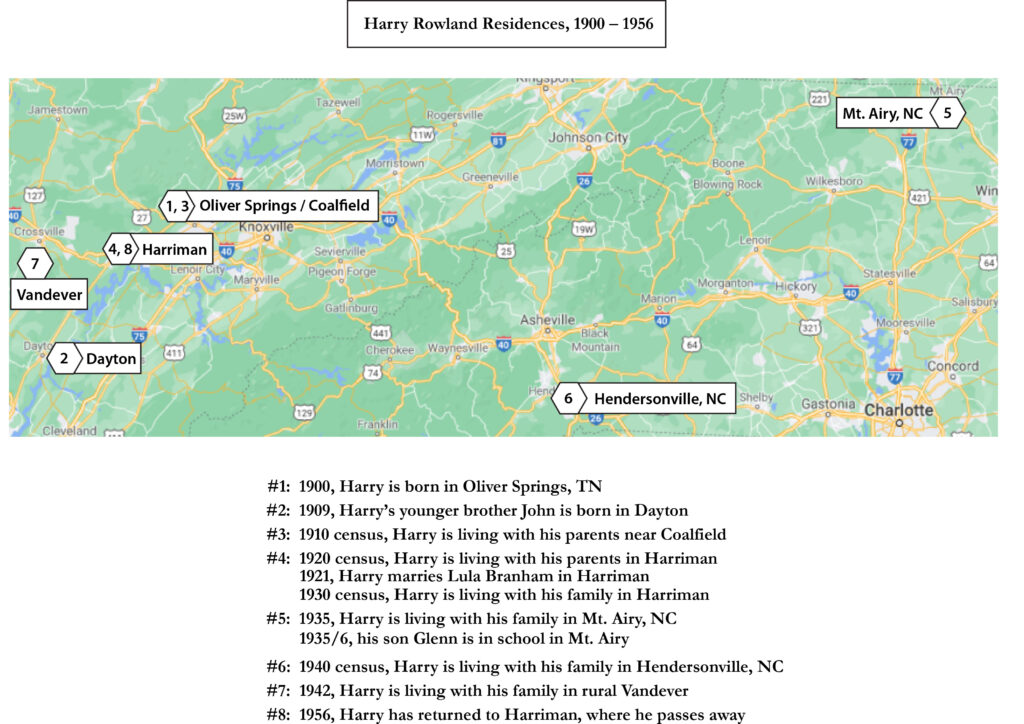

Harry Lee Rowland was the third son and fourth child of John Woods Rowland and Anna Lou Whitus. He was born in 1900 in Oliver Springs, Roane County, Tennessee, and died 55 years later in nearby Harriman. (1) His life was marked by financial setbacks, many caused by the Great Depression, and frequent moves from town to town.

Harry’s birthplace of Oliver Springs was (and still is) tiny, with fewer than 700 residents in 1900. (2) At the time the Rowlands lived there, wealthy visitors came to the area and stayed at the town’s resort hotel, built on top of mineral springs, in order to bathe and drink the waters. After the hotel burned in 1905, its owner chose not to rebuild as the structure had been under-insured. Over time, Oliver Springs and the area around it became dependent on the coal industry for jobs, with the first mine opening in 1904. (3)

Harry may well have begun elementary school in Oliver Springs, given that his brother Roy was born there in August 1906, the year Harry would have started first grade that Fall. By 1909, his parents had moved the family to Dayton in neighboring Rhea County, where Harry’s youngest brother John was born in July that year. We have not yet been able to identify any family members or associates in that county to explain why or how Rhea County was chosen. But regardless, Harry’s formal education ended after he completed third grade that year. (5)

By 1910, however, the family was back in Morgan County, where Harry’s father and two oldest brothers all worked as coal miners. Ten years later, the family was enumerated in the census in the nearby town of Harriman on the Emory River in central Roane County. While Harriman was rather small — only 4,000 residents in the 1920 census — it had a paper mill and two hosiery mills, as well as numerous small manufacturing businesses, which may have served as the attraction that drew them to the town. (6)

The Rowlands lived first on Junction Road, which no longer exists, and then on Carter Street, near the various mills and the railroad yards that moved their goods, and uncomfortably close to the floodplain. Harry’s future wife, Lula Kathryn Branham, lived several blocks away, at #1 Clinton Street, along with her parents, Jesse Branham and Laura Thrasher Branham. Harry and Lula may well have met through the hosiery mill where Harry and his sister Jennie, as well as Lula and her sister Lena Branham Smith, all worked in 1920. Period articles in local newspapers indicate the mill workers participated in a number of social activities, including baseball games and picnics, which could have brought the couple together. (7)

Harry and Lula married in 1921 and had three sons over the next four years. In early 1930, tragedy struck Harry’s small family when their middle son Edwin died six weeks after contracting whooping cough, complicated by measles and then pneumonia. With no antibiotics available at that time, there was little that doctors could do to save his life. (8)

By mid-April that year, Harry had moved his small family from their Walden Street home to a rental at 504 Walker Street on the south side of Harriman and across the Emory River, perhaps as a way to escape sad memories of their lost son. Harry was working as a fixer (mechanic) at the hosiery mill, where he had worked by then for over 10 years. (9)

Beginning in July 1933, a number of workers at the Harriman Hosiery Mill went on a year-long strike, sparked by their decision to establish a local union under the provisions of the National Industrial Recovery Act, part of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal. As a mill employee, Harry would have been among those affected, though we have not yet uncovered documentation as to whether he was a union member himself. As the strike went on, support for the workers gradually diminished among townspeople as the local economy began to suffer. The strike eventually ended in July 1934 when federal officials ruled in favor of the mill owners, leaving many of the strikers without work. (10)

By the following year, Harry and his family were living in Mt. Airy in north-central North Carolina, known today as the hometown of 20th-century actor Andy Griffith. In the mid-1930s, Mt. Airy had about 6,000 residents and, more importantly, a number of factories, including textile and hosiery mills. Given Harry’s long employment at the Harriman Hosiery Mill, this is likely what drew him to the area, especially if he had been directly involved in the strike and unable to find employment in Harriman afterwards. (11)

By 1940, Harry had moved yet again, this time to Hendersonville, North Carolina, a town of just over 5,000 people. In the census that year, Harry was listed as a hosiery mill fixer who had been out of work for five weeks. His wife, Lula, was working full-time as a looper, providing the family’s sole support. The family lived at 110 North King Street, three blocks from Grey Hosiery Mill, which may well have been their place of employment. (12)

The year 1942 found Harry and Lula in yet another location, this time back in Tennessee. They were living south of Crossville, Cumberland County, in the Vandever community, where Lula’s parents had purchased land several years earlier and were enumerated in the 1940 census. Harry and Lula’s son, Glenn, recalled that they had built their home with the help of relatives, because the family had little money. It may be that the family’s economic hardships were due, to some extent, to a possible drinking problem; Lula told her granddaughter that Harry sometimes came home late at night after having had too much to drink with his friends. (13)

After World War II, Harry and Lula moved back to Harriman, where Harry once again got a job at the hosiery mill. He was well known among his friends as an excellent pool player; indeed, when pool sharks came through town, Harry would invariably be summoned to the bar, where he would lull the visitor into a false sense of security by losing a round or two, then upping the bet and winning all subsequent rounds. (15)

He was delighted when his first grandchild was born, six months before he passed away. The hosiery mill where he worked had a pegboard with numbered hooks holding toys and other small goods; employees could pay to draw a number and win whatever was on the hook with that number. Harry bought all the hooks so that he could get a doll that was on display for his new granddaughter. (16)

Harry passed away suddenly in February 1956. An asthma sufferer, he would go to the local hospital for treatment from time to time. It was during one of those visits that he had a heart attack and passed away. He is buried in Harriman’s Walnut Hill Cemetery in a family plot.

Sources:

- Tennessee Department of Public Health, delayed birth certificate, no. #D-148936 (1942), Harry Rowland, Division of Vital Statistics, Nashville, Tennessee; Tennessee Department of Public Health, death certificate, no. #356-03682 (1956), Harry Lee Rowland, Division of Vital Statistics, Nashville, Tennessee.

- Oliver Springs, Tennessee, Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 10 Mar 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oliver_Springs%2C_Tennessee.

- “Early History,” Oliver Springs Historical Society, https://oshistorical.com/history, accessed 27 Aug 2021.

- Tennessee Department of Public Health, delayed birth certificate, no. #D-222955 (1943), Jennie Bell Rowland, Division of Vital Statistics, Nashville, Tennessee; Tennessee Department of Public Health, delayed birth certificate, no. #D-148937 (1942), Roy Hayes Rowland, Division of Vital Statistics, Nashville, Tennessee.

- Tennessee Department of Public Health, delayed birth certificate, no. #58754, Tennessee Delayed Birth Records, 1869-1909 (Vol. 1909 volume), John Wesley Rowland, Ancestry.com, image 445 of 2227, accessed 30 Aug 2021; 1910 U.S. census, Morgan County, Tennessee, population schedule, enumeration district (ED) 51, sheet 16-B, dwelling #437, family #439, John Rowland, accessed via Ancestry.com, 27 Jan 2008; 1940 U.S. census, Hendersonville, Henderson County, North Carolina, population schedule, enumeration district (ED) 45-15, sheet 7-A, dwelling #166, Harvey Roland, accessed via Ancestry.com, 30 Aug 2021.

- 1910 U.S. census, Morgan County, Tennessee, Harriman, population schedule, enumeration district (ED) 51, sheet 16-B, dwelling #437, family #439, John Rowland, accessed via Ancestry.com 27 Jan 2008; 1920 U.S. census, Roane County, Tennessee, Harriman City, enumeration district (ED) 158, sheet 14-A, dwelling #274, family #317, John Roland, accessed via Ancestry.com 27 Jan 2008.

- 1920 U.S. census, Roane County, Tennessee, Harriman City, enumeration district (ED) 158, sheet 11-B, dwelling #219, family #250, Laura Brannam, accessed via Ancestry.com 27 Jan 2008; Kentucky State Board of Health, delayed birth certificate, no. #168267 (1942), Lula Kathryn Branham, Bureau of Vital Statistics, Frankfort, Kentucky; newspaper articles on this topic include “Oakwood Defeats Harriman Outfit,” The Knoxville News-Sentinel, 7 Aug 1933, p 8; also “Two Girls Games At Park Tomorrow,” Knoxville News-Sentinel, 19 Feb 1932, p 19.

- Tennessee State Board of Health, death certificate, no. #3998 (1930), Edwin Earl Rolland, Bureau of Vital Statistics, Nashville, Tennessee.

- 1930 US census, Roane County, Tennessee, Harriman City, population schedule, enumeration district (ED) 73-2, sheet 17-A, dwelling #320, family #367, Harry L. Rowland, accessed via Ancestry.com 30 Aug 2021.

- Patrick D. Reagan, “Harriman Hosiery Mills Strike of 1933-34,” Tennessee Encyclopedia, https://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entries/harriman-hosiery-mills-strike-of-1933-34/, 8 Oct 2017, accessed 14 Aug 2021; W. Calvin Dickinson and Patrick D. Reagan, “Business, Labor, and the Blue Eagle: The Harriman Hosiery Mills Strike, 1933-1934,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly, vol. 55, no. 3 (1996), http://www.jstor.org/stable/42628434, accessed 24 Oct 2021.

- Glenn Rowland school photograph, 1935/36, Mt. Airy, North Carolina, privately held by Donna Rowland Gough, Reston, VA; “The Spencer’s Inc. Mill Redevelopment Opportunity and its Potential Role in Meeting the Housing Needs of Mount Airy and Surry County,” 2010, Master’s Project, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, https://www.mountairy.org/DocumentCenter/View/577/spencer_mill_redevelopment_opportunity_2010?bidId=, accessed 20 Oct 2021.

- 1940 U.S. census, Henderson Co., NC, pop. sch., Hendersonville, ED 45-15, sheet 7-A, dwell. #166, Harvey Roland; Cole del Charco, “Catawba County Hosts ‘The Way We Worked’ Smithsonian Exhibit, WFAE News, 10 Aug 2018, https://www.wfae.org/local-news/2018-08-10/catawba-county-hosts-the-way-we-worked-smithsonian-exhibit, accessed 30 Aug 2021; “Grey Hosiery Mill,” Hendersonville Historic Preservation Commission, http://www.hendersonvillehpc.org/structures/national-register-listings/grey-hosiery-mill/, accessed 30 Aug 2021.

- World War II Draft Cards, 1940-1947, digital images, Ancestry.com, accessed 9 Nov 2012, Harry Lee Rowland, serial #T83, order #T10,488, Cumberland County, Tennessee; 1940 U.S. census, Cumberland County, Tennessee, population schedule, enumeration district (ED) 18-10, sheet 4-B, dwelling #58, J.P. Branham, accessed via Ancestry.com 10 Dec 2012; U.S. Bureau of the Census, Descriptions of Census Enumeration Districts, 1830-1950, NARA microfilm publication T1224 (Washington: National Archives and Records Service, 1978), Roll 114, Cumberland County, 1940 enumeration, p 2, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/5880840, accessed 30 Aug 2021; Glenn Rowland, interview by Donna Rowland Gough, July 1983, notes privately held; notes from conversations with Lula Rowland, compiled 30 Aug 2021 by Donna Rowland Gough, privately held.

- Notes from conversations with Lula Rowland.

- Ibid.

© 2021 Donna Rowland Gough, all rights reserved